Herod’s 1 B.C. Death Demonstrated

by Synchronized Chronology

Gerard Gertoux, Phd

[Editor’s note: This is a immensely learned and valuable study proving beyond contradiction that Herod died in 1 B.C. However, we do disagree with the author’s dating the birth of Christ to September 26, 2 B.C., as it is based upon certain unproved assumptions and contradicts Luke’s gospel, which says Jesus had not turned 30 at his baptism in early November, A.D. 29. We also feel that the evidence favors placing Herod’s death closer to Passover in March, 1 B.C., rather than Jan. 26th as proposed by the author. Even so, the author’s contribution to establishing the true year of Herod’s death is invaluable. Our thanks to Gerard Gertoux for allowing us to post it here.]

The dating of Herod’s death has become the center of a controversy among eminent theologians supporting a date in March / April 4 BCE[1] and historians supporting another date, January 26, 1 BCE[2], based on synchronisms dated by astronomy. This controversy is not insignificant because, as in the case of Galileo, it is between two conceptions of truth: that which is based on the interpretation of religious authorities (theologians) and that based on the interpretation a scientific authority (astronomers)[3]. If we assume, as do historians, that the chronology is the eye of history, only the scientific authority holds the truth in history. Religious authorities do not like that scientists try tointerpret some biblical data. For example, although he was a great scientist, Newton was unable to publish his biblical chronology[4] under penalty of being excommunicated. I have personally been able to verify that the chronology was a sensitive issue because when I included my Master2 inside my doctoral thesis[5], the defense had been canceled twice because of the proposed date of Herod’s death (though validated in my Master2)!

Data to calculate the date of death of Herod the Great come mainly from two historical sources carrying weight: the Gospels and the writings of Flavius Josephus. According to the texts of Luke and Matthew, Herod died shortly after the birth of Jesus (Lk 1:5, 30-31; Mt 2:1-23), which can be fixed in 2 BCE (Lk 2:1-2; 3:1). According to the texts of Flavius Josephus: Herod died after a day that the Jews observe as a fast which happened just before an eclipse of the moon (…); after he had reigned for 34 years from the time when he had put Antigonus to death, and for 37 years from the time when he had been appointed king by the Romans (…); before the Passover (Jewish Antiquities XVII:166-167, 191, 213). Josephus gives even a dozen other synchronisms that enable us to date the reign of Herod (39-2) concordantly, and his death on January 1 BCE. It seems that the first who proposed to date Herod’s death in March 4 BCE was Academician H. Wallon[6]. Based on the coincidence of the partial eclipse of the moon of March 13, 4 BCE with the fast of Esther dated 13 Adar (March 12), he concluded that the reign of 37 years began in 40 BCE and ended in 4 BCE, and, therefore, that the birth of Jesus was to be set for December 25, 7 BCE. This calculation is wrong for three reasons: 1) the fast of Esther in the 1st century did not exist simply because it did not appear until the 12th century, after the works of Maimonides. Josephus also states that on 13 Adar was the Feast of Nicanor (Jewish Antiquities XII:412); 2) according to current astronomical calculations, the eclipse of March 13, 4 BCE had a magnitude of 36% only and had to draw attention that very few people in the early morning when it happened[7]; 3) when we want to reconstruct the life of Herod, if he died on March 4 BCE, we are confronted with a cascade of inconsistencies, if not insurmountable contradictions. It is impossible to make a reconstitution respecting the synchronisms mentioned by Josephus. It is easy to verify that these eleven synchronisms (highlighted) are perfectly consistent and contradict, without exception, the date of Herod’s death in March 4 BCE (column B):

|

|

A |

B |

C |

D |

Event in the life of Herod |

A.J. |

|

-72 |

(-1) |

(-4) |

00 |

|

Herod’s birth (April-July). |

|

|

-47 |

|

|

25 |

|

Caesar arrives in Syria in July -47 and appoints Herod, who was 25 years old, Governor (strategist) of Galilee. |

XIV:158

|

|

-40 |

|

[1] |

32 |

|

Named king at Rome in December -40 by the Roman Senate. |

XIV:389 |

|

-39 |

[0] |

[2] |

33 |

|

March on Jerusalem during in the summer of -39. |

XIV:389 |

|

-38 |

[1] |

3 |

34 |

|

Herod purges Galilee of its brigands. |

XIV:413 |

|

-37 |

[2] |

4 |

35 |

|

Capture of Jerusalem in July -37. In order to reign, Herod makes Antigonus beheaded by the Romans (March -36). |

XIV:487-491 |

|

-36 |

3 |

5 |

36 |

00 |

Actual start of his reign (April -36), Herod mints his first coin dated year 3. |

XX:250 |

|

-32 |

7 |

9 |

40 |

04 |

Beginning of the war of Actium (March -31) at the end of his 7th year. |

XV:121 |

|

-26 |

13 |

15 |

46 |

10 |

In honor of his title «Augustus» gave to Octavius by the Roman Senate in January -27, Samaria is renamed Sebaste. There are 2 years (26-25) famine in Judea from his 13th year. |

XV:297-307 |

|

-25 |

14 |

16 |

47 |

11 |

During these two years of famine, Varro Murana is procurator of Syria and C. Petronius is prefect of Egypt (late -25). |

|

|

-21 |

18 |

20 |

51 |

15 |

At the end of his 18th year (February -20), Caesar arrives in Syria, Herod starts restoration of the Temple. |

XV:354-380 |

|

-11 |

28 |

30 |

61 |

25 |

End of the 192nd Olympiad (June -11) in his 28th year of reign. |

XVI:136 |

|

-4 |

35 |

37 |

68 |

32 |

A testament establishing the kingship of Herod’s sons is approved by Augustus at the end of the legation of Varus (6-4). |

XVII:202-210 |

|

-2 |

37 |

[39] |

70 |

34 |

Beginning of his year 37 in April -2. |

XVII:191 |

|

-1 |

[38] |

|

[71] |

[35] |

Death on January 26, 1 BCE at the age of 70 in his 37th year of reign and 34 years after the death of Antigonus. Year 38 would have started in April -1. |

XVII:148 |

|

1 |

[39] |

|

|

|

Caius Caesar leads troops in Galilee and Varus in Samaria. |

B.J. II:68-69 |

A: year of reign according to a death in -1;

B: year of reign according to a death in -4;

C: age of Herod;

D: year after the death of Antigonus;

A.J. Jewish Antiquities ;

B.J. Jewish War

Several of these synchronisms are easy to check: If Herod was 25 years old in 47 BCE he had to be 70 in 2 BCE, if his 28th year of reign coincided with the end of the 192nd Olympiad (in June 11 BCE) his 37th year of reign began in April 2 BCE, if Antigonus was murdered in March 36 BCE, a period of 34 years later still brings in 2 BCE. The period of 34 years corresponds to the effective reign of Herod (The Assumption of Moses —6).

The first years of Herod’s reign are described by Josephus in great chronological details, which explains the discrepancy between his legal kingship received from Roman Senate in 40 BCE and the beginning of his effective reign in 36 BCE, dated year 3 on his first minting. According to Josephus, Herod came to Rome in winter (Jewish War I:279) at the end of the year 40 BCE (Jewish Antiquities XIV:487), since he conquered Jerusalem in July 37 BCE, just 3 years after his enthronement by the Romans in December 40 BCE (Jewish War I:343; Jewish Antiquities XIV:389). The Roman Senate named him king and celebrated his first day of reign (Jewish War I:285) on January 1, 39 BCE, because the posts of governors were awarded on that date[8]. After the capture of Jerusalem in July 37 BCE, Sossius, the governor of Syria, handed over King Antigonus to Marc Antony. Herod, fearing a possible restoration of Antigonus by the Roman Senate, greased Mark Antony’s palm to kill his rival (Jewish Antiquities XIV:473,487-491). Mark Antony who left Italy for Greece in the autumn of 37 BCE, then went to Antioch which he reached in winter. Antigonus was executed when Herod took power[9]. The Roman historian Cassius Dio (History XLIX:22-23) confirms the chronological[10] data of Josephus. All these synchronisms involve Herod died between April 2 BCE and March 1 BCE[11].

Although Josephus dates Herod’s victory in July 37 BCE, he fixes the beginning of his effective reign in 36 BCE, as he states that Herod ended a Hasmonean era started 126 years earlier (Jewish Antiquities XIV:490). However, as he dates the beginning of the period in -162 the reign of Herod starts therefore in -36 (= -162 + 126). This figure is confirmed by two other indications of Josephus: a) the beginning of his reign is fixed 27 years after the victory of Pompey (Jewish Antiquities XIV:487) dated July -63, that is -36 (= -63 + 27) and b) 107 years before the destruction of the Temple (Jewish Antiquities XX:250) dated August 70, that is -36 (= -107 + 70 + 1, no year 0). A chronological reconstitution of the early years of Herod’s reign follows:

|

year |

|

|

[A] |

[B] |

|

|

-40 |

4 |

I |

|

|

Herod Tetrarch of Judea since December -42 [A]

Antigonus is appointed King of Judea by the Parthians (B.J. I:269) and reigned three years from 0* to 3* [B]. |

|

5 |

II |

||||

|

6 |

III |

0* |

|||

|

7 |

IV |

||||

|

8 |

V |

||||

|

9 |

VI |

||||

|

10 |

VII |

||||

|

11 |

VIII |

|

Herod arrives in Rome. He is appointed king of Judea by the Roman Senate. |

||

|

12 |

IX |

||||

|

-39 |

1 |

X |

January 1st, official beginning of the reign. Ventidius expelled Antigonus from Syria. |

||

|

2 |

XI |

||||

|

3 |

XII |

||||

|

4 |

I |

|

1* |

Herod arrives at Ptolemais |

|

|

5 |

II |

||||

|

6 |

III |

|

General Ventidius loosely cooperates with Herod. |

||

|

7 |

IV |

||||

|

8 |

V |

||||

|

9 |

VI |

[0] |

Herod march to Jerusalem, but must stop because of the Roman army which takes up winter quarters. This act sets accession to the throne. |

||

|

10 |

VII |

||||

|

11 |

VIII |

||||

|

12 |

IX |

||||

|

-38 |

1 |

X |

|||

|

2 |

XI |

||||

|

3 |

XII |

||||

|

4 |

I |

[1] |

2* |

Herod purges Galilee of its brigands. |

|

|

5 |

II |

||||

|

6 |

III |

Sossius supports Herod who conquered Galilee then all the Palestine except its capital.

The arrival of winter prevents Herod to march on Jerusalem. |

|||

|

7 |

IV |

||||

|

8 |

V |

||||

|

9 |

VI |

||||

|

10 |

VII |

||||

|

11 |

VIII |

||||

|

12 |

IX |

||||

|

-37 |

1 |

X |

|||

|

2 |

XI |

Herod lays siege to Jerusalem. |

|||

|

3 |

XII |

||||

|

4 |

I |

[2] |

3* |

|

|

|

5 |

II |

||||

|

6 |

III |

||||

|

7 |

IV |

Herod conquers Jerusalem. |

|||

|

8 |

V |

||||

|

9 |

VI |

||||

|

10 |

VII |

||||

|

11 |

VIII |

||||

|

12 |

IX |

|

Sossius hands over Antigonus to Marc Antony who is bribed by Herod to have him killed. King Antigonus is beheaded when Herod takes power. |

||

|

-36 |

1 |

X |

|||

|

2 |

XI |

||||

|

3 |

XII |

||||

|

4 |

I |

3 |

0 |

Actual start of the reign of King Herod in Jerusalem. The first coin issued by Herod is dated year 3. |

|

|

5 |

II |

||||

|

6 |

III |

||||

|

7 |

IV |

||||

|

8 |

V |

||||

|

9 |

VI |

||||

|

10 |

VII |

||||

|

11 |

VIII |

||||

|

12 |

IX |

||||

|

-35 |

1 |

X |

The first coins minted by Herod after his victory over Jerusalem (in July -37) are dated year 3, wrote L Г in Greek[12] (opposite picture). Since Jewish reigns begin on Nisan 1 (April), this coin is therefore appears in April of 36 BCE. This method of reckoning reign, from Nisan 1 after an accession, was usual for kings of Judea (Talmud Rosh Hashanah 1:1). If Herod died in 4 BCE, year 3 of his reign would be in 38 BCE, two years before his victory, that is unlikely, moreover, at that date Antigonus still ruled Judea. The other synchronisms of the reign of Herod confirm this chronology.

The first coins minted by Herod after his victory over Jerusalem (in July -37) are dated year 3, wrote L Г in Greek[12] (opposite picture). Since Jewish reigns begin on Nisan 1 (April), this coin is therefore appears in April of 36 BCE. This method of reckoning reign, from Nisan 1 after an accession, was usual for kings of Judea (Talmud Rosh Hashanah 1:1). If Herod died in 4 BCE, year 3 of his reign would be in 38 BCE, two years before his victory, that is unlikely, moreover, at that date Antigonus still ruled Judea. The other synchronisms of the reign of Herod confirm this chronology.

Because Herod was 70 years old when he died (Jewish Antiquities XVII:148) and as he was 25 years when he was made governor of Galilee (Jewish Antiquities XIV:158), in July -47, he died in a period from April -2 to March -1. The arrival of Caesar in Syria is narrated by Caesar himself (War of Alexandria LXV-LXVI). After the murder of Pompey (September 28, 48 BCE) he went to Egypt and then arrived in Syria in July -47, according to Cicero (Ad Atticum XI:20). During this stay of just one month, according to Suetonius (Lives of the Twelve Caesar — Caesar XXXV:3), he established a close, Sextus Julius Caesar, as governor of Syria and put Herod in charge of Galilee[13].

|

year |

|

|

age |

|

|

-47 |

1 |

X |

24 |

|

|

2 |

XI |

|||

|

3 |

XII |

|||

|

4 |

I |

Caesar is in Syria and appoints Herod, who is 25, as «governor (strategist)» of Galilee. |

||

|

5 |

II |

|||

|

6 |

III |

|||

|

7 |

IV |

25 |

||

|

8 |

V |

|||

|

9 |

VI |

|||

|

10 |

VII |

|||

|

11 |

VIII |

|||

|

12 |

IX |

|||

|

-46 |

1 |

X |

||

|

2 |

XI |

|||

|

3 |

XII |

|||

|

4 |

I |

|

||

|

5 |

II |

|||

|

6 |

III |

Josephus mentions the age of Herod [of 25 years] in connection with his appointment as «governor» of Galilee, which fixes his birth to -72 in June / July.

Josephus still relates that the battle of Actium took place in the 7th year of Herod’s reign[14] (Jewish Antiquities XV:121). As the war began in March -31[15] and it ended with the victory of Caesar (and Agrippa) against Cleopatra (and Antony) on September 2, 31 BCE, this allows to set the beginning in the 7th year which goes from April -32 to March -31. If we fix the end of the war in the 7th year, not the beginning, the death of Herod would be located (in his 37th year) between April -1 and March 1. Both possibilities (died on January 1 BCE or January 1 CE) clearly contradict a death dated in 4 BCE.

|

year |

|

|

[A] |

[B] |

|

|

-32 |

4 |

I |

7 |

4 |

Octavian gathered his troops at Brundisium and Agrippa took command of the fleet

Beginning of the war of Actium. |

|

5 |

II |

||||

|

6 |

III |

||||

|

7 |

IV |

||||

|

8 |

V |

||||

|

9 |

VI |

||||

|

10 |

VII |

||||

|

11 |

VIII |

||||

|

12 |

IX |

||||

|

-31 |

1 |

X |

|||

|

2 |

XI |

||||

|

3 |

XII |

||||

|

4 |

I |

8 |

5 |

End of the war of Actium. |

|

|

5 |

II |

||||

|

6 |

III |

||||

|

7 |

IV |

||||

|

8 |

V |

Herod rebuilt the city of Samaria and renamed it Sebaste in honour of the emperor (Jewish Antiquities XV:297-299), because Octavian had been awarded the title of Augustus by the Roman Senate on January 16, 27 BCE. The rebuilding of Samaria was probably completed by the end of the year -27[16]. Then, during this year [beginning in January -26], the 13th of his reign (Jewish Antiquities XV:299-307), there was a terrible famine in Judea, which lasted about 2 years and required the intervention of the prefect of Egypt Gaius Petronius [in the early -24][17]. Shortly after the construction of Sebaste appears Varro [Murena] (Jewish Antiquities XV:342-345), the procurator of Syria from -25 to -23[18].

|

year |

|

|

[A] |

[B] |

|

|

-27 |

12 |

IX |

|

|

In honour of Augustus, Samaria is renamed Sebaste by Herod. |

|

-26 |

1 |

X |

|||

|

2 |

XI |

||||

|

3 |

XII |

||||

|

4 |

I |

13 |

10 |

A terrible famine raged in Judea during the 13th and 14th year of Herod.

Varro Murena is appointed as procurator of Syria |

|

|

5 |

II |

||||

|

6 |

III |

||||

|

7 |

IV |

||||

|

8 |

V |

||||

|

9 |

VI |

||||

|

10 |

VII |

||||

|

11 |

VIII |

||||

|

12 |

IX |

||||

|

-25 |

1 |

X |

|||

|

2 |

XI |

||||

|

3 |

XII |

||||

|

4 |

I |

14 |

11 |

Gaius Petronius is appointed as prefect of Egypt. |

|

|

5 |

II |

||||

|

6 |

III |

||||

|

7 |

IV |

||||

|

8 |

V |

||||

|

9 |

VI |

||||

|

10 |

VII |

||||

|

11 |

VIII |

||||

|

12 |

IX |

||||

|

-24 |

1 |

X |

If Herod died in -4, early in his 37th year of reign, his 14th year would go back in -27, date incompatible with the prefecture of Gaius Petronius beginning in late -25.

According to Josephus, the arrival of Caesar in Syria is located after the 17th year of Herod’s reign (Jewish Antiquities XV:354). He added that on this occasion Herod decided to undertake the restoration of the Temple in Jerusalem which is dated in the 18th year of his reign (Jewish Antiquities XV:380) or in the 15th year of his reign [after the death of Antigonus] (Jewish War I:401). If we refuse the precision «after the death of Antigonus», one is forced to admit that Josephus, or a scribe, later made a mistake. Dion Cassius situated the trip of Augustus in Syria in the spring when Marcus Apuleius and Publius Silius were consuls (Roman History LIV:7:4-6), in 20 BCE. Such as Jewish year begins in April, the months of February and March belong to the end of the previous year.

|

year |

|

|

[A] |

[B] |

|

|

-21 |

1 | X |

17 |

14 |

|

| 2 | XI | ||||

| 3 | XII | ||||

| 4 |

I |

18 |

15 |

Caesar arrives in Syria. Herod undertakes the restoration of the Temple and its complete rebuilding. |

|

| 5 |

II |

||||

| 6 |

III |

||||

| 7 |

IV |

||||

| 8 |

V |

||||

| 9 |

VI |

||||

| 10 |

VII |

||||

| 11 |

VIII |

||||

| 12 |

IX |

||||

|

-20 |

1 |

X |

|||

|

2 |

XI |

||||

|

3 |

XII |

||||

|

4 |

I |

19 |

16 |

|

|

|

5 |

II |

Josephus specifies (Jewish Antiquities XVI:136) that the 28th year of Herod’s reign expired (sic) in the 192nd Olympiad [from July -12 to June -11].

|

year |

|

|

[A] |

[B] |

|

|

-11 |

1 |

X |

|

|

|

|

2 |

XI |

||||

|

3 |

XII |

||||

|

4 |

I |

28 |

25 |

End of the 192nd Olympiad. |

|

|

5 |

II |

||||

|

6 |

III |

||||

|

7 |

IV |

|

|||

|

8 |

V |

||||

|

9 |

VI |

||||

|

10 |

VII |

||||

|

11 |

VIII |

||||

|

12 |

IX |

||||

|

-10 |

1 |

X |

|||

|

2 |

XI |

||||

|

3 |

XII |

This high internal consistency of all these chronological data of Josephus indirectly confirms its accuracy.

As noted previously, Josephus gives three chronological indications[19] when Herod died: (1) after a day that the Jews observe as a fast which happened (2) just before an eclipse of the moon (3); before the Passover (Jewish Antiquities XVII:166-167, 213). The Jews were fasting four times a year[20] (Zechariah 8:19): on Tammuz 17, Ab 9, Tishri 3 and Tebeth 10. It is noteworthy that Adar 13 was not fasted at the time because it was the Feast of Nicanor[21] (Jewish Antiquities XII:412). The Mishna (Taanit 2:10, Rosh Hashanah 1:3) also stipulates that there was no fasting at Purim in the month of Adar. The fast of the 7th month (Tishri) was commemorating the murder of Gedaliah and the one of the 10th month (Tebeth) was commemorating the beginning of the siege of Jerusalem by Nebuchadnezzar (2 Kings 25:1, Ezekiel 24:1,2) as recalled by Josephus (Jewish Antiquities X:116). The fast of Tebeth[22] 10 (January 5 in 1 BCE) actually preceded a few days the total lunar eclipse on Tebeth 14/15[23] (9/10 January in 1 BCE)[24].

The Jewish religious year begins on Nisan 1. This particular day coincides with the first visible lunar crescent in Jerusalem after the spring equinox. Dates of equinoxes[25] and of first lunar crescents[26] for years 4 and 1 BCE follows:

|

[autumn equinox] |

[25 September -2] |

[25 September -5] |

|

|

VII |

1st Tishri |

29 September -2 |

2 October -5 |

|

VIII |

1st Heshvan |

29 October -2 |

31 October -5 |

|

IX |

1st Kislev |

27 November -2 |

30 November -5 |

|

X |

1st Tebeth |

27 December -2 |

29 December -5 |

|

XI |

1st Shebat |

25 January -1 |

28 January -4 |

|

XII |

1st Adar |

25 February -1 |

27 February -4 |

|

[XIIb] |

[1st Adar2] |

— |

— |

|

[spring equinox] |

[22 March -1] |

[22 March -4] |

|

|

I |

1st Nisan |

25 March -1 |

28 March -4 |

|

II |

1st Iyar |

23 April -1 |

26 April -4 |

|

III |

1st Siwan |

23 May -1 |

25 May -4 |

|

IV |

1st Tammuz |

21 June -1 |

24 June -4 |

|

V |

1st Ab |

20 July -1 |

24 July -4 |

|

VI |

1st Elul |

19 August -1 |

22 August -4 |

|

VII |

1st Tishri |

17 September -1 |

21 September -4 |

|

VIII |

1st Heshvan |

17 October -1 |

21 October -4 |

|

IX |

1st Kislev |

15 November -1 |

19 November -4 |

The ancient Roll of fasts (Megillat Taanit 18b)[27] sets Herod’s death on Shebat 2 (Megillat Taanit 23a), or January 26 in -1[28]. The date of Alexander Jannaeus’ death is set on Kislev 7, but some believe (without justification) that it could be the date of Herod’s death.

Astronomy enables us to date the events mentioned by Josephus: (1) a memorial fasting followed by (2) an eclipse of the moon and then (3) Herod’s death, three events which succeeded in a short time before Passover:

|

|

|

date |

|

in 1 BCE |

|

in 4 BCE |

|

|

mth. |

(1) fast |

(2) eclipse |

(3) death |

|

# |

|

# |

|

VII |

3 Tishri |

|

|

1st October -2 |

|

4 October -5 |

|

|

VIII |

Heshvan |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

IX |

Kislev |

|

7 Kislev ? |

3 December -2 |

|

6 December -5 |

|

|

X |

10 Tebeth |

|

|

5 January -1 |

YES |

8 January -4 |

|

|

|

|

15 Tebeth |

|

10 January |

Total |

13 January -4 |

|

|

XI |

Shebat |

|

2 Shebat | 26 January -1 |

YES |

29 January -4 |

NO# |

|

XII |

[13] Adar |

|

|

[9 March -1] |

|

[12 March] |

NO# |

|

|

|

14 Adar |

|

|

|

13 March |

Partial |

|

I |

[1st] Nisan |

|

|

[25 March -1] |

|

1 April ?? |

NO# |

|

|

[14] Nisan |

|

(4) Passover |

[7 April -1] |

|

[10 April -4] |

|

|

II |

Iyar |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

III |

Siwan |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

IV |

17 Tammuz |

|

|

7 July -1 |

|

10 July -4 |

|

|

V |

9 Ab |

|

|

29 July -1 |

|

1st August -4 |

|

|

VI |

Elul |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

VII |

Tishri |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

VIII |

Heshvan |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

IX |

Kislev |

|

7 Kislev ? |

21 November -1 |

|

25 November -4 |

|

The agreement is excellent in 1 BCE, but in 4 BCE inconsistencies abound.Indeed, just before Herod’s death there is no Memorial fasting, worse, on Adar 13 is a feast day (Feast of Nicanor) and the traditional date of Herod’s death (Shebat 2) does not work anymore since it is located before, not after it (the date of 7 Kislev is worse).

On the death of Herod, his sons sought the endorsement of Caesar Augustus to legitimize their royalty, as did Herod himself. Josephus explains that in the past: Caesar received the boys [in 20 BCE] with the greatest consideration. He also gave Herod the right to secure in the possession of his kingdom whichever of his offspring he wished (Jewish Antiquities XV:343). Herod being dead on 2 Shebat (26 January -1), the first year of effective reign of his sons could start at Nisan 1 (March 24, -1). Herod Philip did as his father. The coins (below) minted from his first year of reign in -1 are dated year 3, wrote L Г in Greek[29], which referred to Herod’s testament made at the end of the legation of Varus in -4, year being considered as an accession year (without having been co-regency).

This point is crucial to understand the chronology of Herodian reigns. Indeed, fictional accessions, legally back-calculated, were not uncommon at that time[30]. All of the Herods acknowledged receiving their kingdom from Augustus (Jewish Antiquities XVII:244-246). A testament establishing the kingdom of Herod’s sons was written in front of Augustus at the end of the legation of Varus (Jewish Antiquities XVII:202-210). This document served as a reference after the death of Herod to confirm the kingdom of his sons[31]. For that reason, just after the death of Herod, Archelaus rushed to Rome to validate by Augustus the testament of his father who made him king (Jewish War II:1-2).Similarly, Antipas disputed succession to the throne because he was referring to the first testament of Herod, who designated him as king, in his view that testament defeating its codicil (Jewish War II:20). Therefore, that testament, not Herod’s codicils, had to be used to set the beginning of their statutory royalty because only the decision of Augustus, which validated it, was considered as a last resort (Jewish War II:20-21,28). Herod’s sons have been legally established kings (in Rome) before taking office (in Jerusalem). Josephus relates Antipater’s dialogue with his father: And indeed what was there that could possibly provoke me against thee? Could the hope of being king do it? I was a king already (Jewish War I:625-631). If it was only about the certitude of reigning, this explanation would have accused Antipater, because he would have been able to accelerate his accession to the throne by committing parricide, while in recalling that he was King already, Herod’s death did not change anything for him; this argument had already been used in the past to prove his innocence (Jewish War I:503).

This point is crucial to understand the chronology of Herodian reigns. Indeed, fictional accessions, legally back-calculated, were not uncommon at that time[30]. All of the Herods acknowledged receiving their kingdom from Augustus (Jewish Antiquities XVII:244-246). A testament establishing the kingdom of Herod’s sons was written in front of Augustus at the end of the legation of Varus (Jewish Antiquities XVII:202-210). This document served as a reference after the death of Herod to confirm the kingdom of his sons[31]. For that reason, just after the death of Herod, Archelaus rushed to Rome to validate by Augustus the testament of his father who made him king (Jewish War II:1-2).Similarly, Antipas disputed succession to the throne because he was referring to the first testament of Herod, who designated him as king, in his view that testament defeating its codicil (Jewish War II:20). Therefore, that testament, not Herod’s codicils, had to be used to set the beginning of their statutory royalty because only the decision of Augustus, which validated it, was considered as a last resort (Jewish War II:20-21,28). Herod’s sons have been legally established kings (in Rome) before taking office (in Jerusalem). Josephus relates Antipater’s dialogue with his father: And indeed what was there that could possibly provoke me against thee? Could the hope of being king do it? I was a king already (Jewish War I:625-631). If it was only about the certitude of reigning, this explanation would have accused Antipater, because he would have been able to accelerate his accession to the throne by committing parricide, while in recalling that he was King already, Herod’s death did not change anything for him; this argument had already been used in the past to prove his innocence (Jewish War I:503).

According to Flavius Josephus, Herod Archelaus reigned 10 years. The 9th year of his reign (Jewish War II:111), at the end of which he is deposited, is dated 6 CE according Dio (Roman History LV:25:1,27:5) and the beginning of his 10th year (Jewish Antiquities XVII:342), marked by the end of the census of Quirinius, dated 7 CE[32] (Jewish Antiquities XVIII: 26). A chronological reconstitution of the early years of reign of Archelaus follows:

|

year |

|

|

[A] |

[B] |

age |

[C] |

Main event |

|

-3 |

10 |

VII |

36 |

33 |

69 |

[1] |

|

|

11 |

VIII |

||||||

|

12 |

IX |

||||||

|

-2 |

1 |

X |

|||||

|

2 |

XI |

Caesar stated «Father of the Country» (on February 5) |

|||||

|

3 |

XII |

||||||

|

4 |

I |

37 |

34 |

[2] |

Brevarium for the «Inventory of the world» (on May 12)

(Herod was 25 years old on July -47)

Jesus’ birth (on 29 September)

(Massacre of the Innocents on December 25) |

||

|

5 |

II |

||||||

|

6 |

III |

||||||

|

7 |

IV |

70 |

|||||

|

8 |

V |

||||||

|

9 |

VI |

||||||

|

10 |

VII |

||||||

|

11 |

VIII |

||||||

|

12 |

IX |

||||||

|

-1 |

1 |

X |

Herod died on January 26, at the age of 70 years, in his 37th year of reign, 34 years after the death of Antigonus. |

||||

|

2 |

XI |

|

|

|

|

||

|

3 |

XII |

||||||

|

4 |

I |

[38] |

[35] |

|

3 |

Official start of the reign of Herod’s sons. Beginning of the «war of Varus» |

|

|

5 |

II |

||||||

|

6 |

III |

The careers of governors of Syria were listed[33], making it possible to establish chronological synchronisms with the reigns of Herodian kings.

|

year |

Legate of the East |

Governor of Syria |

Reign of Archelaus |

Rector of Caesar (main event) |

Governor of Galatia |

Governor of Germania |

|

|

-10 |

|

M. Titius |

29 |

|

|

|

|

|

-9 |

|

M. Titius |

30 |

|

|

|

Tiberius |

|

-8 |

|

S. Saturninus |

31 |

|

|

|

Tiberius |

|

-7 |

|

S. Saturninus |

32 |

|

|

C. Aquila? |

Tiberius |

|

-6 |

(Tiberius) |

Q. Varus |

33 |

|

|

C. Aquila |

S. Saturninus |

|

-5 |

(Tiberius) |

Q. Varus |

34 |

|

|

S. Quirinius |

S. Saturninus |

|

-4 |

(Tiberius) |

Q. Varus |

35 |

[0] |

(Herod’s testament) |

S. Quirinius |

S. Saturninus |

|

-3 |

(Tiberius) |

S. Quirinius |

36 |

[1] |

|

|

D. Ahenobarbus |

|

-2 |

(Tiberius) |

S. Quirinius |

37 |

[2] |

(census of the world) |

|

D. Ahenobarbus |

|

-1 |

Caius Caesar |

Q. Varus |

[38] |

3 |

M. Lollius |

|

D. Ahenobarbus |

|

1 |

Caius Caesar |

Q. Varus |

|

4 |

M. Lollius |

|

M. Vicinius |

|

2 |

Caius Caesar |

|

|

5 |

S. Quirinius |

M. Servilius? |

M. Vicinius |

|

3 |

Caius Caesar |

|

|

6 |

S. Quirinius |

M. Servilius |

M. Vicinius |

|

4 |

|

V. Saturninus |

|

7 |

(death of Caius C.) |

M. Censorinus |

Tiberius |

|

5 |

|

V. Saturninus |

|

8 |

|

M. Censorinus |

Tiberius |

|

6 |

|

S. Quirinius |

|

9 |

(Archelaus deposed, |

M. Silvanus |

Tiberius |

|

7 |

|

S. Quirinius |

|

10 |

census of his goods) |

M. Silvanus |

Q. Varus |

|

8 |

|

S. Quirinius? |

|

|

|

(S. Pupius?) |

Q. Varus |

|

9 |

|

S. Quirinius? |

|

|

(death of Varus) |

(S. Pupius?) |

Q. Varus |

|

10 |

|

S. Quirinius? |

|

|

|

|

Tiberius |

|

11 |

|

S. Quirinius? |

|

|

|

|

Tiberius |

|

12 |

|

M. Silanus |

|

|

|

|

Tiberius |

|

13 |

|

M. Silanus |

|

|

|

|

|

|

14 |

|

M. Silanus |

|

|

(death of Caesar) |

|

|

Two important synchronisms with the governors of Syria confirm a death of Herod in 1 BCE: 1) the census of Quirinius in 2 BCE and 2) the War of Varus in 1 CE.

According to Luke 2:1: Now at this time Caesar Augustus issued a decree for a census of the whole world to be taken. This census — the first — took place while Quirinius was governor of Syria. Justin located this event 150 years before the time he was writing his book (Apology I:34:2; I:46:1) or at the very beginning of our common era since he wrote about 148-152. The historian Paul Orosius precisely date the census of Augustus in the year 752 of Rome (Histories against the pagans VI:22:1; VII:3:4) or in 2 BCE. According to Josephus: Quirinius, a Roman senator who had proceeded through all the magistracies to the consulship and a man who was extremely distinguished in other respect, arrived in Syria, dispatched by Caesar to be governor of the nation and to make an assessment of their property. Coponius, a man of equestrian rank, was sent along with him to rule over the Jews with full authority. Quirinius also visited Judaea, which had been annexed to Syria, in order to make an assessment of the property of the Jews and to liquidate the estate of Archelaus. Although the Jews were at first shocked to hear the registration of property, they gradually condescended (…) but a certain Judas, a Gaulanite (…) threw himself into the cause of rebellion (…) Quirinius had now liquidated the estate of Archelaus; and by this time the registrations of property that took place in the 37th year after Caesar’s defeat of Antony at Actium were complete (Jewish Antiquities XVIII:1-4,26). Such registration of property (not people) does not correspond to the one performed at the birth of Jesus, for at least two reasons. Luke knew this record associated with a revolt and mentions it apart (Acts 5:37) specifying, as Josephus, that during this (second) registration «Judas the Galilean» rebelled (Jewish Antiquities XX:102)[34]. He also noted that Jesus’ birth occurred during the «first record», which implies the existence of a second (recounted in the Acts). In addition, he does not mention any revolt during the first census. The first registration( ![]() απογραφη), as the census of Apamea, was made to know the number of citizens and it is not to be confused with the one implemented in Judea by Quirinius when he came to ensure the liquidation of property of Archelaus after his disgrace, and of which Josephus says it was followed by an «evaluation (

απογραφη), as the census of Apamea, was made to know the number of citizens and it is not to be confused with the one implemented in Judea by Quirinius when he came to ensure the liquidation of property of Archelaus after his disgrace, and of which Josephus says it was followed by an «evaluation (![]() αποτιμηοις)» of property. This two-step operation did not have the same nature, nor the same goal, or the same geographical scope as the previous one. It was conducted according to the principles of the Roman capitation and not according to Hebrew customs, and only covered the sole Judea, not Galilee.General censuses were performed every 5 years (= 1 lustre) as can be deduced from those reported by Cassius Dio[35].

αποτιμηοις)» of property. This two-step operation did not have the same nature, nor the same goal, or the same geographical scope as the previous one. It was conducted according to the principles of the Roman capitation and not according to Hebrew customs, and only covered the sole Judea, not Galilee.General censuses were performed every 5 years (= 1 lustre) as can be deduced from those reported by Cassius Dio[35].

According to the periodicity of 5 years, we see that the first census, the one mentioned by Luke, fits exactly in the list of censuses, while the second one mentioned by Josephus, and in the book of Acts, was only a local census (in Judaea):

|

year |

Cens |

Characterisc of the census |

Reference |

|

-28 |

|

Census with lustration mentioned in the Res Gestae (census of Gaul and Spain) |

Res Gestae —8 (Cassius Dio LIII:22) |

|

-27 |

|

||

|

-26 |

|

||

|

-25 |

|

||

|

-24 |

|

||

|

-23 |

|

Census postponed to -22 due to the serious illness of Augustus (performed by Paulus Aemilius Lepidus and L. Munatius Plancus) |

Cassius Dio LIV:2 |

|

-22 |

|

||

|

-21 |

|

||

|

-20 |

|

||

|

-19 |

|

||

|

-18 |

|

Census postponed, Augustus having refused to be censor. |

Cassius Dio LIV:10 (Lex Iulia) |

|

-17 |

|

||

|

-16 |

|

||

|

-15 |

|

||

|

-14 |

|

||

|

-13 |

|

The census lasted from -13 to -11. (census of Gaul and Spain) |

Cassius Dio LIV:25-30 (Cassius Dio LIV:32) |

|

-12 |

|

||

|

-11 |

|

||

|

-10 |

|

||

|

-9 |

|

||

|

-8 |

|

Census with lustration mentioned in the Res Gestae |

Res Gestae —8 |

|

-7 |

|

||

|

-6 |

|

||

|

-5 |

|

||

|

-4 |

|

||

|

-3 |

|

Inventory of the world Census (registration) mentioned by Luke 2:1

|

Titulus Venetus (Res Gestae —15) |

|

-2 |

|

||

|

-1 |

|

||

|

1 |

|

||

|

2 |

|

||

|

3 |

|

||

|

4 |

|

Cens limited to Italy (Lex Aelia Sentia)

Census of Quirinius in Judaeamentionned in Acts 5:37 |

Cassius Dio LV:13

Jewish Antiquities XVIII:1-4 |

|

5 |

|

||

|

6 |

|

||

|

7 |

|

||

|

8 |

|

||

|

9 |

|

Census planned but suspended because of the disaster of Varus |

(Lex Papia Poppaea) Cassius Dio LVI:18 |

|

10 |

|

||

|

11 |

|

||

|

12 |

|

||

|

13 |

|

||

|

14 |

|

Census with lustration mentioned in the Res Gestae |

Res Gestae —8 |

|

15 |

|

||

|

16 |

|

||

|

17 |

|

||

|

18 |

|

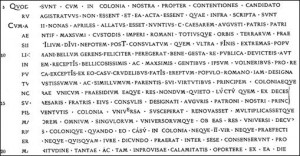

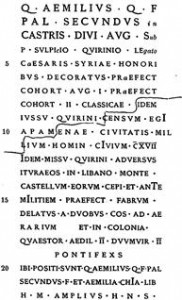

The census of Luke is in agreement with Roman history[36]. Since the census of Quirinius in Apamea is about people and was carried out in Syria[37], while the one described by Josephus was a census of goods (to liquidate the possessions of Archelaus) carried out in Judea, they have nothing in common, either in purpose or by the area covered. The census of Apamea should be compared with the one of Luke. The registration of the knight Aemilius Secundus, visible on the Titulus Venetus (CIL III 6687, ILS 2683), describes a census of Quirinius in Syria. According to this text, knight Q. Aemilius Secundus fulfilled his service in Syria under the authority of Quirinius, legate of Caesar (governor) in Syria, who had himself received the insignia of triumph (honorary distinctions) after the campaign against the armies of Taurus «Homonadenses» in Galatia (from 5 to 4 BCE).

Q[uintus] Aemilius Secundus s[on] of Q[uintus], of the tribe Palatina, who served in the camps of the divine Aug[ustus] under P. Sulpicius Quirinius, legate of Caesar in Syria, decorated with honorary distinctions, prefect of the 1st cohort Aug[usta], prefect of the cohort II Classica. Besides, by order of Quirinius I made the census of 117 thousand citizens of Apamea. Besides, sent on mission by Quirinius, against the Itureans, I took their citadel on Mount Lebanon. And prior military service, (I was) Prefect of the workers, detached by two co[nsul]s at the «aerarium [The State Treasury]». And in the colony, quaestor, aedile twice, duumvir twice, pontiff.

Q[uintus] Aemilius Secundus s[on] of Q[uintus], of the tribe Palatina, who served in the camps of the divine Aug[ustus] under P. Sulpicius Quirinius, legate of Caesar in Syria, decorated with honorary distinctions, prefect of the 1st cohort Aug[usta], prefect of the cohort II Classica. Besides, by order of Quirinius I made the census of 117 thousand citizens of Apamea. Besides, sent on mission by Quirinius, against the Itureans, I took their citadel on Mount Lebanon. And prior military service, (I was) Prefect of the workers, detached by two co[nsul]s at the «aerarium [The State Treasury]». And in the colony, quaestor, aedile twice, duumvir twice, pontiff.

Here were deposited Q[uintus] Aemilius Secundus s[on] of Q[uintus], of the tribe Pal[atina], (my) s[on] and Aemilia Chia (my) freed.

This m[onument] is excluded from the inh[eritance].

In his cursus honorum the knight Secundus details his career. This type document describes the distinctions obtained in a chronological order. The inventory referred in the inscription, performed under the orders of Quirinius, is not the one made in year 6 CE which was due to the removal of King Archelaus and was confined in Judea, not Syria. Second, the census of the city of Apamea in Syria (which was a registration)[38] is followed by the mission in Ituraea [a small country full of brigands]. Now the citadel of the Itureans [whose name was Chalcis] was taken before (not after) Herod’s death[39], as indicated by Strabo (Geography XVI:2:18-20) and Josephus (Jewish Antiquities XV:342-364)[40].

The Breviarium of Augustus (in 2 BCE) was used to establish a new type of census to compile statistical data[41] (digestiones) obtained, inter alia, «to show off the wealth of Rome.» In his eulogy, the first version was publicly displayed in the temple of Mars Ultor on May 12, 2 BCE, the Emperor Augustus announced the breviarium totius imperii[42] that he should let at his death in 14 CE, which contained according to Tacitus: a description of the resources of the State, of the number of citizens and allies under arms, of the fleets, subject kingdoms, provinces, taxes, direct and indirect, necessary expenses and customary bounties. All these details Augustus had written with his own hand (Annals I:11,4). This inventory had no known antecedent. It is this latter aspect of Breviarium that has most struck the ancient writers: Tacitus speaks of a «picture of the public power,» Cassius Dio (Roman History LVI:33:2) a «general assessment» and Suetonius (Augustus CI:6) a «state of affairs of the Empire».

Such an inventory had to concern «all the inhabited earth» at that time. Client Kings were treated essentially as Roman governors, according to Suetonius (Augustus LX). Thus, Judea, although it was a client kingdom, could hardly oppose the will of the emperor. In fact, it was placed under the supervision of the governor of Syria (Jewish Antiquities XIX:338-342). Herod had therefore to collaborate with Quirinius as did the city of Apamea. This census was ordered by the emperor, but its execution could not be done with the help of Herod. The Jewish kingdom listed the men «in the house of their fathers» (Numbers 1:18), that explains the movement of Joseph from Nazareth to his hometown of Bethlehem (Luke 2:3-4) to be registered[43], because the Jewish administration listed men according to their patrimonial place (Leviticus 25:10).

This new conception of census is well described by Emperor Claudius, who writes: The census had no other object than the official statement of our resources (Table Claudienne de Lyon 78-80). We read in the Souda, a famous Byzantine encyclopedia dated 10th century: Caesar Augustus, emperor, who chose twenty citizens distinguished by their morals and integrity, sent them to all parts of the world subject to the empire, to make the identification of people and goods. The corpus of agrimensores even specifies: According to the books of the surveyor Balbus, who at the time of Augustus, brought together in folders plans and measures, identified by him, of all the provinces[44]. Ancient authors such as Isidore of Seville (Etymologiarum sive originum V:36.4) and Cassiodorus (Varia III:52,6-8) were struck by the statistical aspect of this census aimed to describe all the resources of the empire. This special registration which took place at the time of Jesus’ birth, unique in all the Roman annals (an inventory of the whole world!), had been announced in the biblical text: In his place will rise a king who will send an exactor [census taker] in the most beautiful part of the world [Palestine] (Daniel 11:20, Zadoc Kahn). Jesus’ birth has been associated with an important event, easy to identify and date. The testimonies of the historians of the first six centuries[45] are also unanimous in dating the birth of Jesus around 2 BCE. Clement of Alexandria (The Stromata I:21:145). place the birth of Jesus 194 years before the death of Commodus (December 31, 192 CE) and Tertullian (Against the Jews VIII:11:75) place it in the 41st year of the reign of Augustus[46] (which began from the second triumvirate of October -43, made official a few weeks later[47] by the law lex Titia, on November 27, -43) and 28 years after the death of Cleopatra (August 29, -30)[48]. By combining these data, the birth of Jesus must be fixed in 2 BCE in a period between September 1 and October 30[49]. Jesus is born about 4 months before the death of Herod.

The biography of Quinctilius Varus is succinct[50], but he played an important role in the life of Herod, since, in presence of the emperor (in 4 BCE), he negotiated an agreement to grant the inheritance to his sons, and it is still him who was instructed to quell the various rebellions after his death. Herod’s death should be dated to 1 BCE, because the intervention of Varus, after the death of Herod, is described as a war by Josephus (Against Apion I:34), yet the only war mentioned in the Roman archives in this region and at that time (around January 1 CE) is the one conducted by Caius Caesar.

|

Sequence of events |

Reference |

date |

|

Testament of Herod determining the kingship of his sons. |

B.J. I:646-647 |

July -4 |

|

Last testament of Herod (codicil). |

B.J. I:664 |

21 January -1 |

|

Herod’s death |

B.J. I:665 |

26 January -1 |

|

Archelaus goes to Rome to make confirm his kingship. |

B.J. II:1-4 |

|

|

Departure of Governors for their province. |

|

April/June -1 |

|

Feast of the Passover. |

B.J. II:10 |

6 April -1 |

|

Varus arrives soon into Syria at the request of Archelaus. |

B.J. II:16 |

|

|

Antipas leaves for Rome to obtain confirmation of his kingship mentioned in Herod’s testament rather than in his codicil. |

B.J. II:20 |

|

|

Auguste reads the reports of Varus and Sabinus and sits with Caius C. |

B.J. II:25 |

|

|

Varus, the governor of Syria, announces a Jewish revolt, represses it, leaves for Antioch, leaving a legion in Jerusalem. |

BJ II:40 |

|

|

Feast of Pentecost. |

B.J. II:42 |

28 May -1 |

|

Caius leaves for the East with a pro-consular imperium. |

|

July -1 |

|

Sabinus fears for the legion left in Jerusalem and calls Varus for help. |

B.J. II:45-54 |

|

|

Revolt fomented by Ahab, and Judas son of Hezekiah. |

B.J. II:55-56 |

|

|

Rebellions fomented by Simon, then Athrongaios. |

B.J. II:57-65 |

|

|

Varus returned to Syria with two additional legions. |

B.J. II:66 |

|

|

Beginning of the war of Varus under the auspices of Caius. |

C.A. I:34 |

|

|

Caius leads troops in Galilee and Varus control those in Samaria. |

B.J. II:68-69 |

|

|

Varus ends «his war», Festival (of Booths), Sabinus leaves Jerusalem. |

B.J. II:72-79 |

November -1 |

|

Caius is appointed consul at Rome |

|

1 January 1 |

|

Herod’s sons are officially enthroned by Augustus, according to the testament of July -4. |

B.J. II:93-100 |

|

The various denominations for the title of «governor» (of Syria) were dependent on the period 8 BCE to 17 CE. They are in agreement with the previous chronology:

After the death of Herod, Varus, governor of Syria (as strategist, not as commandant), quelled several rebellions, including the one of Simon narrated by Tacitus (Histories V:9). Josephus prefers to speak of war because all the legions of Syria were mobilized. Indeed, in this time Syria had been three major wars: the ones of Pompey (in 63 BCE), of Varus (Against Apion I:34) and of Titus (in 66-70). This war of Varus was conducted under the auspices of Caius (Cassius Dio LV:10:18), imperial legate of Caesar in the East from 1 BCE to 4 CE. It has been granted to him in the inscription on a cenotaph. The career of Gaius Caesar, the grand-son of Augustus, was very brief. An inscription[51] in a cenotaph of Pisa (CIL XI 1421; ILS 140) provides his cursus honorum and mentions as the only honorary remarkable action: a war beyond the outer limits of the Roman people during the year of his consulate (lines 8 to 10 of the inscription below). It is therefore important to identify this war and to date it.

Velleius Paterculus, who was an eyewitness to the career of Gaius Caesar, said: Shortly after this Gaius Caesar, who had previously made a tour of other provinces, but only as a visitor, was dispatched to Syria. On his way he first paid his respects to Tiberius Nero, whom he treated with all honor as his superior. In his province he conducted himself with such versatility as to furnish much material for the panegyrist and not a little for the critic (Roman History II:100). Velleius says that the career of Caius in the East began with Syria but he does not specify what were his «actions deserving of praise». Cassius Dio (Roman History LV:10a:4) says that Caius resided in Syria in the year of his consulate (beginning on January 1, 1 CE), coinciding with the war mentioned in the inscription on the cenotaph of Pisa. Caius left Rome for the East at the expiration of the powers of Tiberius (July 1 BCE)[52] but because of his age (18 years old when he left Rome), Augustus put in charge Marcus Lollius as rector of Caius, from 1 BCE until his disgrace in 2 CE, and then Quirinius.The usual date of January 29, 1 BCE, marking the departure of Caius Caesar to the East[53], as evidenced by a fragment of the Fasti of Praeneste, could be link with the departure of Tiberius to the East[54] (enacted on January 29, 22 BCE) to retrieve the Roman standards taken by the Parthians, according to Suetonius (Life of Tiberius IX:1), not to Caius Caesar. The Roman standards were recovered about December 21 BCE, according to Cassius Dio (Roman History LIV:9).

According to Roman historians, Caius came to the East with a proconsular imperium (previously held by Tiberius) primarily to address issues of Parthia and Armenia, and for this reason that his actions in Syria are seen by them as secondary. The only Latin author to talk about the campaign in Syria is Pliny (Natural History XII:55), which recounts a glorious campaign of Caius in «Arabia», general term for Syria (Natural History VI:141), which involved Aretas IV, Arab king of the Nabataeans (Jewish War II:68-70). This self-proclaimed king (in 9 BCE) was endorsed by Rome (in 1 CE) thanks to his support for the army of Varus after the death of Herod[55]. The role of Caius Caesar beside Varus was more honorary than decisive because Josephus (Jewish War II: 25.68) briefly presents him either as the son of Agrippa or as the friend of Varus. According to Tacitus (Annals II:30:4, IV:66:1), Quirinius and Varus were indeed intimate of Augustus and therefore of Caius.

Conclusion: All historical synchronism of the reign of Herod (a dozen) provide, without exception, a date of the death toward the end of the year 2 BCE. In addition, the lunar eclipse mentioned (unique in all the work of Josephus) is dated January 9/10, 1 BCE, 5 days after the fast of 10 Tebeth, which is a remarkable confirmation. In 4 BCE, not only there was no fasting, but a feast (Nicanor). Finally, the census of Quirinius is well documented as it coincides with the inventory of the world in 2 BCE and the War of Varus, after Herod’s death, under the auspices of Caius Caesar, is dated in 1 CE. I presented these findings to Maurice Sartre, a leading French academic expert on these issues. His letter-writing response was scathing: I was an ignorant impertinent (because I had dared to challenge his assertions by arguments), furthermore, I had absolutely to refer to his works to discover the basic elements of history.

In his view[56]: The passage in Luke throws a trouble spot since he places the census directly related to the birth of Jesus: it is to fulfill the obligation to be identified so that Joseph and Mary would have gone to Bethlehem and Jesus would be born. This can only have occurred long after the death of Herod because John the Baptist, older than a few months, was born and was designed at the time of Herod. There was considerable information on the epilogue of Luke, without finding a solution that saves it. Let alone the date, in fact all of the information appears unbearable. Not only there never was a general census of the Empire (except for Roman citizens), but even if the census was confined to the Roman province of Syria, there is no reason why the subjects of client State of Antipas were concerned (…) how Luke could he be so wrong by combining the census — if it took place in 6 AD — with the birth of Jesus, which occurred, according to Matthew 2.1, at the end of the reign of Herod, probably in 6 or 5 BC (…) After the departure of P. Quinctilius Varus, governor since 7 BC and still in place at the time of Herod’s death (he repressed the revolt in Jerusalem), he was replaced directly by L. Calpurnius Piso Pontifex, who remained in place until 1 BC. Therefore, there is no vacancy for a first term of Quirinius.

According to this prestigious and powerful academic[57], in fact all of the information [from Luke] appears unbearable (…) how Luke could he be so wrong. Who to believe, Luke or Sartre? In any case, one of them is either an incompetent historian or, worse, a liar. When you know that there is no evidence to prove the presence of L. Calpurnius Piso Pontifex[58] in Syria[59], the answer is obvious.

[1]E. Schurer— The history of the Jewish people in the age of Jesus Christ

Edinburgh 1987 Ed. T &T Clark Ltd pp 326-327.

J.P. Meier— A Marginal Jew

New York 1991 Ed. Doubleday pp. 414-415.

R.E. Brown— The Birth of the Messiah

New York 1993 Ed. Doubleday pp. 166-167.

[2]W.E. Filmer — The Chronology of the Reign of Herod the Great

in: The Journal of Theological Studies, Vol. XVII. Oxford 1966 pp. 283-298.

A.E. Steinmann— When Did Herod the Great Reign? in: Novum Testamentum Vol. 51 (2009) pp. 1-29.

[3] J. Oppert— La chronologie biblique fixee par les eclipses des inscriptions cuneiformes

in: Revue archeologique 18 (1868) pp.1-32.

[4] The Chronology of the Ancient Kingdoms Amended (London 1728).

[5] Ph.D in Archaeology and History of Ancient Worlds http://www.theses.fr/sujets/?q=Gertoux+Gerard

[6] H. Wallon— Memoire sur les annees de Jesus-Christ

Paris 1858 Ed. Comptes Rendus Academie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres.

[7] 4 BCE = -3* http://eclipse.gsfc.nasa.gov/LEcat5/LE-0099-0000.html

[8]C. Saulnier — Histoire d’Israel

Paris 1985 Ed. Cerf p. 207.

[9]R. Marcus— Josephus. Jewish Antiquities, Books XIV-XV

Cambridge 2004 Ed. Harvard University Press page 255 note e, page 479 note b.

[10]E. Schurer — The History of the Jewish people in the age of Jesus Christ

Edinburg 1987 Ed. T & T Clark Ltd pp. 281-288.

[11]J. Finegan — Handbook of Biblical Chronology

Massachussetts 1999 Ed. Hendrickson pp. 299-301.

[12]J. Maltiel-Gerstenfeld — 260 Years of Ancient Jewish Coins

1982 Tel Aviv Ed. Kol Printing Service Ltd pp. 125-131.

[13]E. Schurer — The History of the Jewish people in the age of Jesus Christ

Edinburg 1987 Ed. T & T Clark Ltd pp. 248,270-276.

[14]This sentence is ambiguous because Josephus does not say if this is the beginning or end of the battle.

[15] J.M. Roddaz — Marcus Agrippa — Les arcanes de la puissance

Farnese 1984 Ed. Ecole Francaise de Rome pp. 159-166.

[16] G. Goyau— Chronologie de l’Empire romain

Paris 2007 Ed. Errance p. 10.

[17] S. Jameson— Chronology of Aelius Gallus and C. Petronius

in: The Journal of Roman Studies 58 (1978) pp. 71-84.

[18]R. Szramkiewicz — Les Gouverneurs de Province a l’Epoque Augusteenne Tome II

Paris 1976 Ed. Nouvelles Editions Latines pp. 460,525.

[19]A fourth chronological indication be deduced from the fact that Herod ate an apple before he died (Jewish Antiquities XVII:183), because this fruit is harvested in late August and its shelf life is maximum five months. Therefore it is possible to eat apples in Judea until the beginning of February of the following year. If Herod died in March -4 he would have eaten just before dying, a rotten apple!, unless to postulate a miraculous preservation for seven months, which is impossible according to agronomists.

[20]The Talmud (Taanit 4:6) only describes the fasts of 17 Tammuz and 9 Ab.

[21]This feast of Nikanor on 13 Adar was formerly known as the feast of Mordecai (2Maccabees XV: 36).

[22]According to the Jerusalem Talmud (Taanith 3:1) this fast was observed only in Judea.

[23]Astronomy requires to match the eclipses of the moon with the full moon days.

[24] http://eclipse.gsfc.nasa.gov/LEcat5/LE-0099-0000.html

[25]http://www.imcce.fr/fr/grandpublic/temps/saisons.php

[26]Day 1 = new moon + 1 http://www.imcce.fr/fr/grandpublic/phenomenes/phases_lune/index.php

[27]W.E. Filmer — The Chronology of the Reign of Herod the Great

in: The Journal of Theological Studies Vol. XVII. Oxford 1966 p. 284.

H. Lichtenstein — Die fastenrolle eine untersuchung zur judisch-hellenistishen geschichte

in: Hebrew Union College Annual Cincinnati 1931-32 pp. 271-280.

[28]J. Finegan — Handbook of Biblical Chronology

Massachussetts 1999 Ed. Hendrickson p. 295.

O. Edwards — The Time of Christ

Edinburgh 1986 Ed. Floris Books p. 59.

[29]J. Maltiel-Gerstenfeld — 260 Years of Ancient Jewish Coins

1982 Tel Aviv Ed. Kol Printing Service Ltd p. 144.

[30] E.J. Bickerman -Notes on Seleucid and Parthian Chronology

in: Berytus VIII (1943) pp. 73-83.

[31]W.E. Filmer — The Chronology of the Reign of Herod the Great

in: The Journal of Theological Studies, Vol. XVII. Oxford 1966 pp. 283-298.

[32]Consular years used by Cassius Dio was reckoned from January 1 to December 31, 6 CE, but the 37th of Actium was reckoned from September 2, 6 CE to September 1, 7 CE. The 9th year of Archelaus was reckoned from April 17, 6 CE to April 6, 7 CE.

[33]R. Szramkiewicz — Les Gouverneurs de Province a l’Epoque Augusteenne Tome I

Paris 1972 Ed. Nouvelles Editions Latines pp. 86-91, 234.

R. Szramkiewicz — Les Gouverneurs de Province a l’Epoque Augusteenne Tome II

Paris 1976 Ed. Nouvelles Editions Latines pp. 220,498-499,522-527.

[34]The magician named Theudas (Jewish Antiquities XX:97-98) who was executed in 44 CE is different from the seditious of the same name mentioned in Acts V:36 because he was killed prior to Judas the Galilean in 6 CE, and he was not a magician (if he was a magician his function would have been mentioned as in the case of Simon in Acts 8:9).

[35]The part of his history covering the period from -6 to 4 has unfortunately been lost.

[36] T. Corbishley — Quirinius and the Census : a Re-study of the Evidence

in: Klio 29 (1936) pp. 90-92.

[37] It is noteworthy that the Latin word census written ??? is epigraphically attested (CIS II,1,n—198) in the Nabataean kingdom for the first time in 1 BCE (E. Paltiel — Vassals and Rebels in the Roman Empire in: Latomus vol. 212, Bruxelles 1991, pp. 26-27).

[38] D. Kennedy— Demography, The Population of Syria and the Census of Q. Aemilius Secundus

in: Levant 38 (2006) pp. 109-124.

[39]The text of Luke 3:1 confirms that Herod had actually Ituraea since his son Philip had inherited: Herod [Antipas] was tetrarch of Galilee, his brother Philip was tetrarch of the lands of Ituraea and Trachonitis.

[40]Lysanias (Jewish Antiquities XV: 344) was king of Itureans, according to Cassius Dio (Roman History XLIX: 32; LIV: 9).

[41]C. Nicolet — L’inventaire du monde

Paris 1988 Ed. Fayard pp. 156-157, 190.

[42] According to Suetonius (Augustus 28:1-29:3) and Cassius Dio (Roman History LIII :30-31), Augustus had already prepared a draft of the Breviarium after his serious illness (in -23).

[43]In the 1st century the «head tax» for the Temple is called kensos (census) in Matthew 17:25.

[44] F. Blume, K. Lachmann, A. Rudorff — Schriften der Romischen Feldmesser

Berlin 1848 p. 239 (cf. Suidae lexicon I. Lipsiae 1928 Ed. A. Adler p. 293).

[45]Around 148-152, Justin fixed Jesus’ birth 150 years earlier (Apology I:46:1).

Around 170-180, Irenaeus of Lyons situated it in the 41st year of the reign of Octavian (Against Heresies III: 21:3).

In 204, Hippolytus of Rome dated Jesus’ birth on December 25 in the 42nd year of the reign of Augustus (Commentary on Daniel IV:23).

In 231, Origen dates it in the 41st year of Augustus’ reign 15 years before his death (Homilies on Luke 3:1).

In 325, Eusebius fixes it in the 42nd year of Augustus’ reign and 28 years after Cleopatra’s death in 30 BC (Ecclesiastical History I:5:2).

In 357, Epiphanius dates it in the year when Augustus XIII and Silvanus were consuls (Panarion LI:22:3).

In 418, Paul Orosius dates it in the year 752 of the founding of Rome (Histories against the pagans VI:22.1).

[46]Ancient writers reckoned the reign of Augustus not from January -27, but from October -43 when Octavian, later Augustus, formed the second triumvirate. The 42nd year of Augustus began (at the end of his 41st year), so in October -2.

[47] Appian— Civil Wars IV:5-7.

[48] G. Goyau— Chronologie de l’Empire romain

Paris 2007 Ed. Errance p. 7.

[49]According to Luke 1:5-8, John the Baptist was conceived in Abijah’s section, 8th out 24 (1 Chronicles 24:7-8). Passover in -3 took place on April 29; the 1st section (Jehoiarib) began Saturday 11, May; the 8th section began on Saturday 29, June; Jesus was conceived 6 months after John the Baptist (Luke 1:36) on Monday 30, December -3 and was born 273 days later on Monday 29, September -2.

[50]R. Szramkiewicz — Les Gouverneurs de Province a l’Epoque Augusteenne Tome II

Paris 1976 Ed. Nouvelles Editions Latines pp. 434-435.

[51]Inscriptiones Latinae antiquissimae ad C. Caesaris mortem in: Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum Vol. I.

[52] F. Hurlet — Les collegues du prince sous Auguste et Tibere

1997 Rome, Ecole francaise de Rome pp. 110-111.

[53] P. Arnaud— Transmarinae provinciae : reflexions sur les limites geographiques et sur la nature des pouvoirs en Orient

in: Cahiers du Centre Gustave Glotz 5 (1994) pp. 221-253.

[54] The inscription could be read as: mar[cello et arruntio con(n)s(ulibus) instead of: maxi[mo c. caesar princ(eps) iuvent(utis) (see M. Spannagel — Exemplaria principis. Untersuchungen zu Entstehung und Ausstattung des Augustusforums in: Archaologie und Geschichte 9, Heidelberg, 1999, p. 26).

[55]If Herod died in -4, Aretas IV (-9 to 40) would have been recognized as king by Rome only 4 years later, that is unlikely. This is not possible unless one assumes the unlikely solution: after Aretas helped Herod, a Roman vassal king, Augustus would have annexed the country of Aretas from 3 to 1 BCE (which would have been a punishment!), then Caius Caesar would have restored his kingdom in 1 CE (M. Sartre— L’Orient romain. Paris 1991 Ed. Seuil pp. 30-31).

[56] M. Sartre — D’Alexandre a Zenobie. Histoire du Levant antique

Paris 2001 Ed. Artheme Fayard pp. 540,542.

[57]As a member of the editorial board of major journals of French history he is the guarantor of «orthodoxy» of articles.

[58]Some scholars have tried to identify the anonymous who was governor of Syria twice in the inscription of Tibur (CIIL XIV 3613 = ILS 918) to Calpurnius but it is impossible because he was prefect of Rome from 13 to 32 CE and this prestigious function (Annals VI:10) would not appear at the end of his cursus honorum. The anonymous can only be Quirinius as demonstrated by Theodor Mommsen.

[59]R. Szramkiewicz — Les Gouverneurs de Province a l’Epoque Augusteenne Tome II

Paris 1976 Ed. Nouvelles Editions Latines pp. 383-384.